Over the course of the past few months, no subject has been a bigger concern to the world than the global Coronavirus pandemic. All aspects of society have had to deal with the challenges of this crisis. The National Library has launched a dedicated web archive collection, in order to capture the different aspects and consequences of the Covid-19 on the Internet. Even if the collection is not concluded yet, it is time to show first results of what we captured. However, we don’t just want to bombard our readers with numbers and statistics, but also wanted to talk to people who have been especially active in their sector during this crisis. Therefore, we asked Serge Tonnar about his experiences in the past months, how his activities have continued online and about his stance on social media.

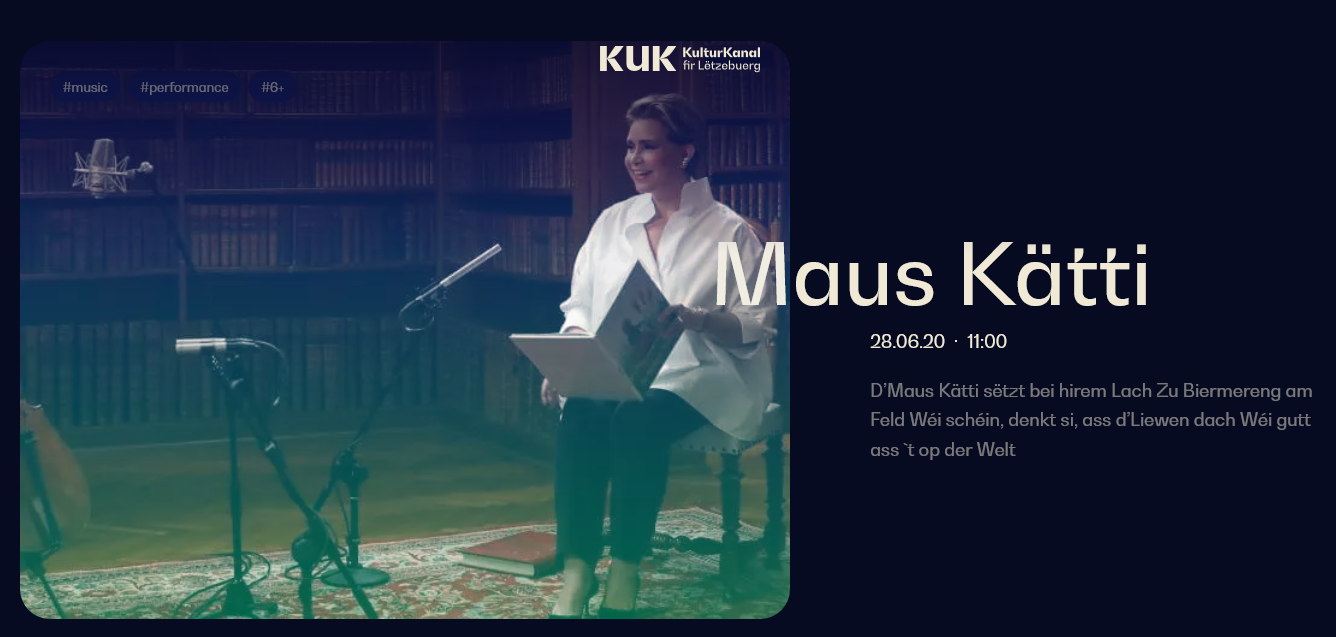

Photo ©Jean Huot/Ed.Binsfeld

Almost overnight, 99% of our professional and social lives had to move to the Internet. How profound has this change been for you?

At first, the transition was not about being online, but first of all about being at home. After that, everything shifted to the Internet. As an artist, I have been working with online technologies for a long time. Online music productions, my YouTube-channel since 13 years – I have been using the Internet for my work a lot, so the changeover was not as dramatic. I launched several projects, because the performing arts had completely disappeared. The goal was to offer artistic performances over the Internet and to give artists an opportunity to work. That idea also caught on in other places, when everyone started working from home and that’s when all the Zoom meetings started.

Was that a positive or negative experience for you?

I think that this situation has pros and cons. The advantages are: you don’t have to travel as much anymore for meetings, which is both more ecologic and time-saving. On the other hand, when Email and the Internet were first introduced, people were able to work faster, but in the meantime, you are also supposed to work much faster. In the past, people wrote letters, which you had to bring to the post office, send it, wait for 2 days, the other person had to read it, and if everything went well, you had your answer a week later. Today, people are getting nervous if they don’t get a reply to an Email within 10 minutes. That’s the disadvantage, where instead of saving time, we increase the work load. When you used to have 2 meetings a day, one in the morning, one in the afternoon, you may have 5, 6 or 7 a day, and that’s where it starts to become unhealthy.

On Tonnar.lu, you describe yourself as a “silencefiller”. The initiatives from Maskénada, Live aus der Stuff and KUK, de Kulturkanal have contributed to fill in the gaps. Does the need for these platforms stem from the Coronavirus crisis, or did these gaps on the web already exist before?

The need for these platforms became more noticeable during quarantine. We realised that no other means of working were possible and quickly tried to find a way to act within the strict conditions, by launching Live aus der Stuff. Everybody had to stay at home, you couldn’t send a technician to someone’s house or get a cameraman for a production, the artists simply used their phones to stream via Facebook from their living room. That became a huge success, to a degree I didn’t expect. This also showed that some things will remain important after the crisis, which were also overdue before: namely the accessibility of culture over the Internet. We try to produce, publish and control our content over the Internet, which means not only to post things on YouTube, Facebook and other Internet-giants. The Kulturkanal has grown from that idea.

A new access for the audience?

It’s all about reaching people and democratising culture. Here, everyone can watch, even if you can’t afford tickets to the Philharmonie. We realised that people discover new artists and forms of artistic expression over these channels. There is a direct link from the artist to the audience, without detours, censorship, organisers, cultural infrastructures or somebody else’s choices. It was only afterwards, that I realised that I was following the same principle at the beginning of my career. For my first two albums in Luxembourgish in 2003 and 2008, I had to try to get my songs on the radio stations, where I was simply ignored, if not even boycotted. This left very little chances for success. Only after I started putting songs on YouTube and Facebook, I started to become more successful, because you could reach your audience directly. Among musicians, this phenomenon is already known for quite some time, at least for 15 years. It is also clear that those who are most successful online, will also draw the biggest crowds to their concerts. However, there are other cultural sectors, like performing arts and classical music, who are only now discovering these possibilities, because they were more reticent, or functioning according to cultural coding, which is now not valid anymore. These sectors now know that they have to use digital means to reach their audiences. We don’t know yet how this is going to play out, but in any case, the need to reach people in an original way, free of charge, was born during the crisis. While there are monetised approaches in this business, you also sometimes just have to hand out presents, and musicians have been doing that for a long time. With a YouTube Video, you won’t earn anything, except if your views are in the millions, which is merely impossible for Luxembourg artists. You know however, that you will get something back, when people come to see your shows and maybe buy your CDs.

Free access to culture: Would you say that the audience’s appreciation has changed? Has culture gained a new significance in our society?

The emotional appreciation for Live aus der Stuff was overwhelming: When the concerts were sent to people’s homes with the most simple methods and you had people burst into tears of joy, because this sense of community was back. Also the appreciation for Luxembourg artists has increased enormously. People were really asking for more. You could even observe it in the media, where all of a sudden you had special programs, whereas before, artists had to beg for airtime, or even to be acknowledged. So we have a better appreciation, even if people didn’t have to pay for anything. If you have to pay for something, that doesn’t guarantee its impact and cultural value. People would have been happy to pay, were constantly offering to pay for Live aus der Stuff, but the answer was always: No, this is for free, get used to it! Luxembourgers are not always used to that: If it’s free, it can’t be any good. Therefore, there are other ways to support artists, and there is still a lot of unused potential to do that online. Maybe we will even see this next year on the Kulturkanal, via direct patronage of artists, where fans can become sponsors. These models are already being used abroad and I think the audience here is ready to show their support in a way, where everyone is allowed to give what they want, even if you don’t have a lot of money.

The artist’s control over his contents online is an important argument for archiving the web. If the platforms we are using, were to disappear tomorrow, all of our content would be gone as well. Was it a conscious decision to move away from Facebook towards the Kulturkanal?

Yes, it was about having your own platform. Although we don’t know how long it will last. At the moment we only have guaranteed financing for 6 months. If there is no prolongation, then that’s it. It was more important for us to keep control over the content, without being censored. We had problems on Facebook, where companies like Sony or Warner Music thought that the music Jean Müller was playing in his living room belonged to them. Through an algorithm, your content is immediately blocked. Then it’s up to you, to prove your innocence, although it should be the other way around. We wanted to avoid this kind of situation, but we are still streaming on Facebook, because you have to go where people will see it and we want the program to remain popular, to reach the audience. If we were to be blocked on Facebook, the channel will continue on our site, where you can also replay all the videos. However, I don’t think a lot about archiving. I am an artist and not an archivist. As an artist, I perform art live on stage, in the moment, which is immediately gone. That is how I handle my archives as well. If something is gone, then it’s gone. Maybe I will see things differently when I’m older.

If you wanted to explain our society to someone from the future through the Internet: What role would social media play in that context?

Facebook is the most interesting platform, because all the discussions, quarrels and polemic happens here, while on Twitter, people only exchange short sentences and quick reactions. Instagram is more of an aesthetic format, where not a lot of discussions are taking place. People should also save their own pages more often, and even govern the access to their accounts post mortem.

What subject areas would you like to see represented in the web archive?

As an artist, I think it would be important to capture everything that has something to do with artistic creation. But also alternative currents as well, because most popular things are being preserved in one way or another. It should also be as easy as possible for artists to submit their contents and to know which institution to talk to.

You are very active on Facebook, not only as an artist, but also as a person taking a stance on many social issues. If we were to look back at Serge Tonnar in the web archive, would there be areas that should be separated, or is everything part of a whole?

That is a philosophical question. By the way, I recently deactivated my private Facebook account once again, because I need some distance from time to time. If you are a public figure, it is difficult to separate private and professional aspects on social media. In the beginning, you might think: My profile is private, and page represents me as an artist. Pretty quickly you realise, that when you have reached the limit of 5000 friends, you don’t know all of these people and they are not your friends, so you are not in your privacy anymore. At some point you have to separate yourself completely between the public figure and the real person in privacy, who is completely unknown. People are also projecting their positive and negative prejudices onto you. Often, a dispute ensues, while people are attacking you personally, often with insults below the belt and severe threats. If you are still identifying with the virtual Serge Tonnar, you will not be able to cope. I had to make a radical break, which was also quite liberating, because you rise above the negativity. Therefore, I would say: Social networks and privacy don’t go together. Regardless if you are a public figure or not.